Fidesz’s Survival Strategies: How Might the Party Cling to power?

Alex Faludy games out some of the possibilities currently being discussed among Hungary’s commentariat.

Fidesz’s fear of losing office has been the focus of a run of recent H.O. posts. Today I’ll honour an earlier promise and game out some of the party’s possible moves to forestall defeat by unfair means.

This piece makes no claim to originality. The scenarios are simply ‘in the air’ in Budapest: discussed speculatively in cafes and over dinner tables by journalists, think-tankers, diplomats and the general public. Where I know of a published source, I’ve linked to it —but apologies in advance for any omissions. Mostly, what appears below integrates the perspectives I’ve heard of diverse contacts addressing the same topic over coffee (and sometimes cake).

N.B. Fidesz likely hasn’t settled on a course of action but, instead, is currently evaluating different possibilities. Further, the scenarios aren’t mutually exclusive and may be pursued successively: one scheme yielding to another if the first doesn’t bring the polling results desired or if it has to be abandoned following backlash (c.f. the draft ‘Transparency Law’). The list is also note exhaustive: new scenarios, and variations on existing ones, are emerging constantly.

1) The election happens, but without Magyar

Until recently, this was the most visible scenario. The proposed (but oddly stalled) Lex Magyar, mentioned in my previous post, would open the way to removing Peter Magyar from the race by creating a back-door to voiding his immunity as an MEP. This would make it possible to pursue criminal proceedings against him viz a technically deficient asset declaration, alleged past insider-trading etc. Fidesz communication is also building up a narrative re his alleged collusion with Ukrainian intelligence, something which might develop into a pretext to disqualify him on ‘national security’ grounds. Not only could doing so prevent Magyar from running, it could even stop him from campaigning for a replacement TISZA candidate.

Investigative detention in Hungary can be long: suspects are often held for months while police continue their research and debate with prosecutors about whether there’s enough evidence to proceed to trial. Fidesz wouldn’t need to actually prosecute Magyar (who could even be released without charge soon after the election). Given TISZA’s extreme centralisation, however, his temporary absence would paralyse the party —rendering it unable to campaign effectively. Meanwhile, photos of Magyar being taken away in handcuffs could be useful to Fidesz’s propaganda apparatus.

The strategy carries risks in terms of outcry and possibly even civil disobedience by Magyar’s enraged supporters. However, Călin Georgescu’s recent exclusion from Romania’s presidential election on grounds of foreign interference and (even more) similar moves against Marine Le Pen in France because of her party’s financial irregularities might give Orbán cover for the move.

2) The election happens, but without Orbán

A mirror variant, leaked to investigative journalist Szabolcs Panyi (and mentioned by H.O.‘s Ábel Bede) involves Fidesz swapping Orbán, at least nominally, for a different Prime Minister candidate: János Lázár. All, however wouldn’t be as it seems: Orbán would still be pulling the strings.

Indeed, a constitutional amendment could be expected to strengthen the presidency at the expense of the premiership, with Tamás Sulyok making way for Orbán on request. The possibility of this scenario occurring pre-election is heightened if Fidesz thinks there’s no way to prevent defeat, but

a) Wants to hedge against the full consequences of that defeat

and

b) thinks it can manipulate the electoral system to prevent TISZA obtaining a 2/3 majority.

In favour of the ‘bate and switch’ hypothesis is the fact that Orbán has tried something like it before. In 2006, between the two rounds of that year’s parliamentary election, Orbán briefly floated the idea that the moderate conservative ex-politician Péter Ákos Bod (MDF Economy Minister 1990-4, but in academia by 2006) should replace him as the prime minister candidate. Orbán did so recognising that Fidesz was underperforming thanks to his own image problems and, also, in the hope of mending fences with MDF —which had just withdrawn its support.

However, I doubt that today’s choice would, as suggested, be János Lázár. Lázár’s divisiveness within Fidesz would make it hard enough to form a campaign around him. But there’s another problem: not only does Lázár have trust problems horizontally (with colleagues), but also vertically (with Orbán). Between 2018 and 22, he was dropped from his top ministerial role and sent off for a period in the wilderness precisely because Orbán suspected him of building up an independent power base.

If Orbán wants a straw man for his own power, even if only temporarily, it would need to be someone whose instinctive loyalty he could trust or whom he felt he could dominate on account of their personal weakness. That suggests he’d be more likely to go for Gergely Gulyás or Tibor Navracsics. Both men would also be easier to sell to wavering Fidesz moderates and undecided voters, echoing the 2006 ‘Bod strategy’.

3) Tisza wins, but is then hobbled.

Fidesz may have plans to stymie a TISZA government should defeat be unavoidable. This could take either a ‘soft’ or a ‘hard’ form.

The ‘soft’ form relies on Fidesz recalibrating the electoral system such that, while TISZA would take office, it would lack a 2/3 majority. Theoretically, this is impossible because the Fundamental Law prohibits changes to constituency (electoral district) boundaries in the year before a general election. However, given that the Fundamental Law has been amended 15 times since 2011 it’s unlikely that the government would feel squeamish about bringing the figure up to a nice even number.

Fidesz can’t do much in terms of further domestic gerrymandering, which it has already got down to a fine art, but it might manage some new tricks like creating ‘virtual constituencies’ for Hungarian’s living in neighbouring countries and in the global diaspora (to date only entitled to a list vote). This would require some finessing, given that Hungarians who’ve moved to Western Europe tend to be hostile to Fidesz. However, the virtual constituencies can (like domestic ones) probably be drawn and weighted such that unfavourable possibilities are minimised.

Fidesz has traditionally had strong support among ethnic-Hungarians in adjacent countries and has effectively captured the structures of Hungarian diaspora organisations across N. America. It’s also conceivable that the party might be able to clip TISZA of a 2/3 with help from the, nominally non-aligned MPs representing Hungary’s Roma and Swab (ethnic-German) minorities, who have consistently voted with Fidesz across its years in office.

The ‘hard’ version was floated at the weekend in an opinion piece by retired constitutional court judge Béla Pokol in Fidesz’s mouthpiece Magyar Nemzet. It builds on the ‘soft’ version (presuming that efforts to deprive Magyar of a 2/3 majority have been successful) but goes a step further. A constitutional amendment would create a 5-person ‘Constitutional Council’ comprising the President of the Republic, President of the Constitutional Court, President of the Curia, Prosecutor General, and President of the Court of Auditors.

If a majority of the Constitutional Council’s members believed the Prime Minister was endangering the constitutional system developed by Fidesz the body would have powers (variously) to: remove the Prime Minister without a parliamentary vote of confidence, suspend the operation of the legislature, temporarily assume executive authority in place of the cabinet and, to instigate new elections. It should be observed en passant that this ‘council of presidents’ bears a certain passing resemblance to the Presidential Council of the Hungarian People’s Republic, under which both its proposer and Orbán grew up.

While not a formal legislative proposal the article indicates the sorts of options being considered in government circles. Given the place of Magyar Nemzet within Fidesz’s communications apparatus, it cannot have been printed without clearance at a very high level. While not a statement of intent, it likely represents an exercise in testing the waters: seeing what Fidesz MPs and opinion formers will tolerate without committing the party, thereby forestalling any embarrassing re-run of the ‘Transparency Law’ debacle.

4) There is no election

Cancelling, or more technically ‘postponing’, the election could be done on the basis of a state of emergency.

This possibility was first suggested to me by a senior retired Hungarian diplomat who I consulted while reporting for another outlet. His view was that the recent scandal re alleged Hungarian espionage in Transcarpathia (which involved a resident Ethnic-Hungarian purportedly researching the availability of weapons on the local black-market), “tells us rather more about Fidesz’s plans for Hungary than its plans for Ukraine”. Indeed, he continued: “I don’t think we can rule out the possibility that Orbán might provoke – or just simulate – a small ‘border incident’ early next year.”

No troops would need to cross in either direction, but a false-flag incident could be contrived with local sympathisers firing into Hungary, giving the Hungarian army an excuse to fire into Transcarpathia. At this point, the Ukrainian army might feel obliged to return fire, — if only symbolically.

The hostile build-up of government messaging about Ukraine in the last 3 weeks, especially in the PM’s radio interviews, appears to support the idea. In particular, Orbán has said, repeatedly, that Ukraine’s intention to create a 1 million-man-strong army in response to the Russian aggression poses a risk to its Western neighbours.

This strategy might face problems of plausible deniability and backlash within Hungary and even within governing parties. As one contact pointed out “it is important to the self-identity of many people at the top of Fidesz that they do actually win elections.” Another difficulty is that this sort of military adventure might be a step too far for Hungary’s EU and NATO partners. At worst, it could risk the suspension of mutual security guarantees.

A softer (but perhaps more effective) sanction could be refusal to accept Hungary’s newly appointed diplomatic and political representatives as the lawful holders of their respective offices. In fact, preventing elections by this method could give the EU a route to deploy Article 7 restrictions on Hungary de facto without having to navigate the cumbersome path needed to do so de jure.

Alternatively, more than one contact have suggested that Putin might, on his own initiative, rescue Orbán via a wave of terrorist incidents or of cyber attacks on key infrastructure. This would give an equivalent excuse to declare a state of emergency but might enjoy higher plausible deniability given the frequency of Russian hybrid-warfare attacks in other European NATO members.

Moscow would thereby protect its own interests given Hungary’s present status as a proxy for Russia inside NATO and EU structures. It would also mean Russia could continue to enjoy a safe forward base inside the Schengen Zone for its intelligence services, which at present operate from Hungary with impunity.

***

The last point would be a depressing one on which to end. So, instead, let me mention something hopeful. Lately, Hungary’s financial media has abounded with reports of NER* magnates making strangely large capital withdrawals from businesses they’ve acquired through questionable government concessions or which have flourished only through rigged public procurements.

As personal initiatives, these withdrawals differ from the scramble of 2021-2, when Fidesz used the machinery of government to enact a centralised programme of asset transfers as insurance against defeat. Yet, these financial decisions arguably indicate just how much people with inside knowledge fear that the game is up. The fact that some of the stories focused on withdrawals by Orbán’s family members and also by Lőrinc Mészáros (widely deemed a proxy for the PM’s own wealth), is notable.

No one would be happier than I if none out of scenarios 1-4 came to fruition. As you may have gathered, I worry intensely that they might but, as the old saying goes: “In Hungary even pessimism doesn’t work.”

* NER = Nemzeti Együttműködés Rendszere (System of National Co-Operation), Fidesz’s own term for the regime it has created.

Alex Faludy

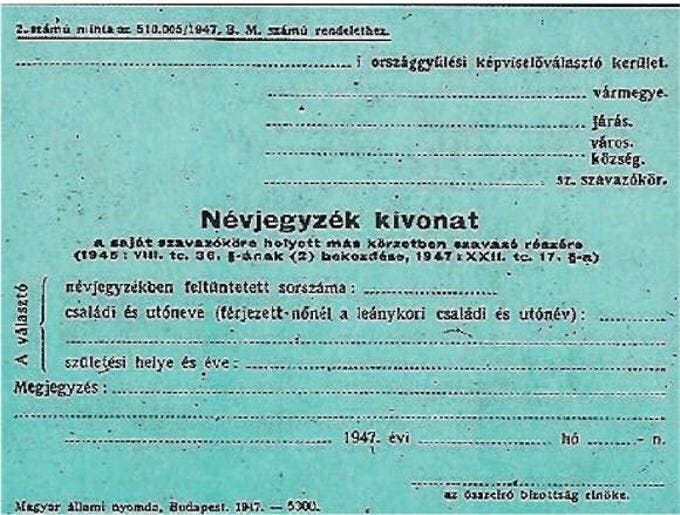

I wonder why you did not consider outright voting fraud? Not a scandalous 99% pro-Fidesz return, but juuust enough for it to form a government even if they cannot attain a two-thirds majority. It would be far less messy than other options being discussed. And when it happened recently in Georgia, Orbán rushed there to congratulate the cheating Georgian government in person, signalling his approval (and possibly his intentions too). Yes, huge popular protests have ensued in Georgia, but a) they haven't changed a thing, and b) cannot the Hungarian government rely on the generally smaller demos in Hungary for confort?

Swap out "bate" for "bait" when you get the chance, eh ?

Grim reading !