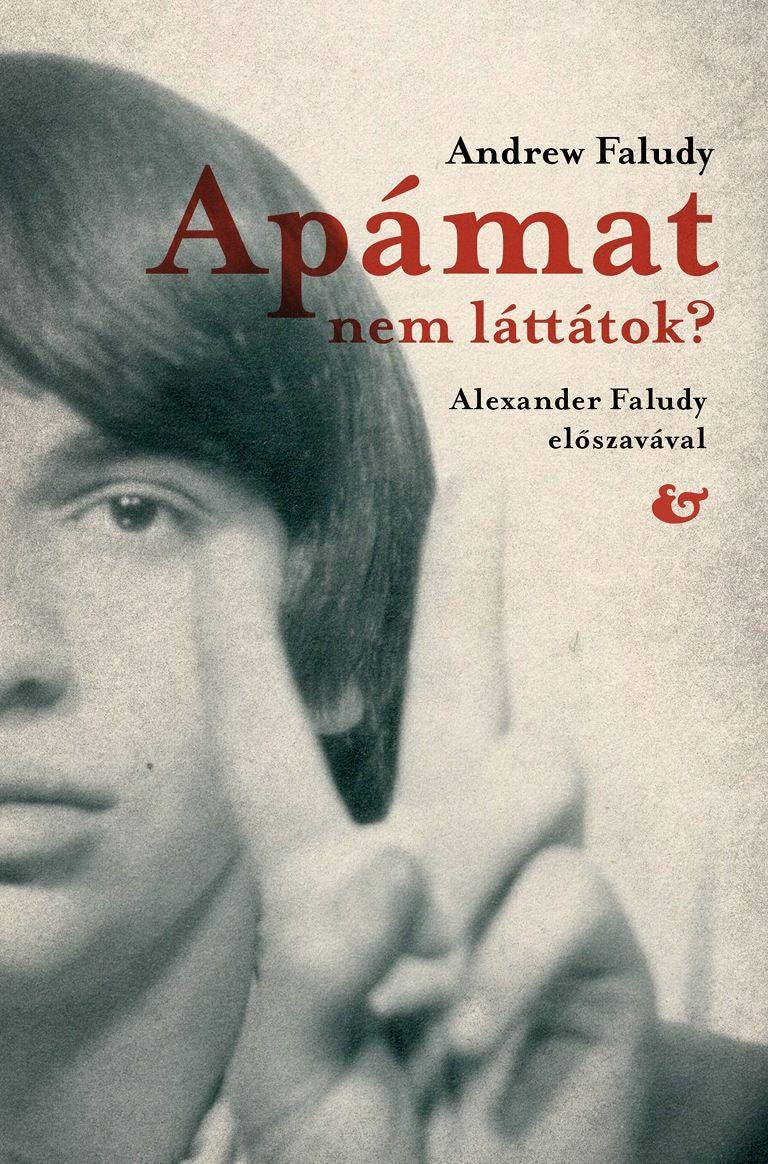

Andrew (András) Faludy (1955-2010) was the only child of the prominent dissident writer György Faludy. The family fled Hungary after the 1956 Soviet invasion but in 1970 Andrew, aged 15, returned to study amid a thaw in the Cold War. His memoir Apámat nem láttátok? [Has Anyone Seen My Dad?] was republished in Hungarian this June by Ampersand kiadó.

***

The atmosphere on the train to Hungary could not have been more different. The carriage was an old Stalinist East Block crate. In my compartment, a Bulgarian student carefully rolled up a wad of purple 100 forint notes purchased at a whacking discount in Vienna, and stuffed them into the ashtray as we approached the border.

Watchtowers. A real iron curtain of barbed wire to keep Westerners from invading the socialist paradise. And I in no man's land.

At Hegyeshalom khaki clad figures armed with rifles surrounded the train. The Bulgarian student was taken away to be body searched. As we pulled out of the station he returned and collected his money from the ashtray.

Through the dirty glass of the window I had my first view of the land of my birth. I do not remember, I do not remember the hospital where I was born.

Giant sunflowers glared down from fields on either side of the track. A peasant urged his unwilling horse forward. Three shabby men stood by a fire in a brazier. We stopped at small stations painted the colour of Coleman's English Mustard.

Finally, with a metallic squeal of pain, the train literally ground to a halt at Budapest's Eastern Railway Station. It was Sunday, 6 September 1970, and in my pocket I had just £4 and a voucher for 1500 Hungarian Forints.

***

Budapest

After rattling a mile or two down the cobbled thoroughfare towards the fin de siecle suburb, the art deco tram deposited me very near my destination, May 1st Street. Its absurd name had been imposed to mark the bogus annual Communist festival in which the workers were supposed to demonstrate their gratitude to Comrade Stalin. Originally, it had been Hermina Street - and would be so again, one day.

My grandparents had once occupied the whole of the top floor, until it had been forcibly sub-divided into three flats under the two people to a room rule introduced by the communists. It was just as well that the population, which was disinclined to breed, had remained static because there was just nowhere to put them all.

A third of my grandparents' former flat was occupied by my Calvinist godmother, Vica (soft "c") along with her son, daughter-in-law and her grand-daughter. Fortunately, as my grandmother was also in residence, only Vica's son, Géza was about - his wife and daughter having gone to visit friends in the country.

Géza opened the door. I must have looked a sight, dishevelled after thirty-six hours on a train, with long hair, hippy clothing and a pile of luggage.

It was immediately apparent that we did not have a common language. My attempts to explain who I was foundered on the anglicised pronunciation of my surname. Perplexed, he ushered me into the main room, a high-ceilinged piece of faded elegance. It seemed vaguely familiar: I had been there before, but I could not remember anything about it. I had an opportunity to look around while he went off to make coffee. On Vica's shelf I found a photograph of myself as a small child.

When Géza returned, I pointed at the picture, and then, slowly, to myself.

Géza flung his arms around me as a prelude to propelling me in the direction of a restaurant for a much-appreciated meal - I had not eaten properly for some time.

The International Institute

At the International Institute, although the other students paid nothing, a minimal termly figure - I think £100 - was agreed in my case: this included tuition, board and lodging. My grandmother paid the bill before departing for England, and I began life under the grey veil of Communism, or Socialism as they now preferred to call it.

Imagine a society in which, if you wanted to buy a dark green jumper all the shops stocked the same design and colour, a shade of bilious lime, and you have communism. Hungarian communism, that is; in Poland there would be no pullovers at all, not even of any kind, not for ready money either, because the shops would contain nothing except pine doorknobs. Still, the Poles were well off compared to the Russians whose shops contained nothing at all. I remember a documentary about a Russian couple who had managed to get out to Vienna, where they looked in the window of a cookware shop. Gazing in wild surmise the woman asked her husband whether it was an exhibition or what. She had to be persuaded that it was a shop. They were not from the bottom of the pile, either - he was a university professor.

Anybody wanting anything had to queue for hours. The queues of the period have long passed into history, having been immortalised at the time through a series of jokes designed to help people to cope with fatigue of having to wait for hours for something perfectly ordinary. Czech joke:

Q: What is a hundred metres long, has two hundred legs, and eats cabbages.

A: A meat queue in Prague.

Hungarians were infinitely better off, and their more comfortable way of life was reflected in humour which had a softer edge.

Hungarian joke:

Two worms are out for a stroll on the Lenin Boulevard when they spot some chestnut purée in a café window.

"Look!" says one worm to the other, "Group Sex!"

This joke used to infuriate me because of the casual mention and implied acceptance of "Lenin Boulevard". After 1989 Lenin Boulevard was renamed after Maria Theresa, and Elizabeth, Empress of Austria, Queen of Hungary. In other words, we were back to where we had been before the communists arrived. I may safely write it now, and you may safely read.

The mass boredom through uniformity under communism was almost as bad as the political repression, which by 1970, although in principle clearly intolerable, had assumed a much milder and more deceptive form.

Such were the circumstances under which I began at the International Institute. It was more than a mere language school, rather a propaganda instrument of Soviet colonial policy through the medium of education. Of the thousand odd students I would be not only the only one under eighteen, but the sole citizen of a country neither in the Soviet bloc nor a third world target for ideological harassment.

The Institute was situated in the middle of nowhere out on Budaorsi Ut, next to the American Military Cemetery and a Budapest University Hall of Residence. The main building was a concrete lump thrust up into the sky, and crammed full of foreign students who were by now so numerous that many had to be housed elsewhere.

They came from:

Argentina

Bulgaria

Congo

East Germany

Estonia

Nigeria

Poland

Russia

Vietnam (North only)

This list is far from complete - I just can't remember any more. The largest proportion - about six hundred - came from North Vietnam. A boat load of Cubans was expected hourly but never arrived. Perhaps the Romanians would not let them sail up the Danube. There were no Czechs - the previous year there had been two who had failed their exams in 1969 and had had to retake, but in the Prague winter all Czechs had been cancelled.

There were so many Poles, Nigerians and Vietnamese that they had to be taught in a variety of groups. I was placed in a tiny class of East Bloc remnants. At the back there were two very pasty Estonian girls with shocking complexions (no doubt diet influenced); there were two Russians, a woman called Gaia (whose name was the best thing about her) and a mysterious young chap with a neatly trimmed moustache who resembled a nineteenth century cavalry officer. There were perhaps one or two more whom I have forgotten and some Bulgarians: Stefanka and an older woman (she seemed impossibly ancient, but must have been under thirty), married to a Bulgarian living in Hungary. Her name was Krasimura Nikolova.

I sat next to Krasi and would not have been able to cope without her because initially the language of instruction was Russian. The teacher, Mrs Maroti, had a smattering of English but Krasi was spectacularly fluent and whispered a flawless simultaneous translation in my ear whilst also attending to her own learning needs. If you're out there reading this, Krasi, thanks for your help - I would have been completely lost without you.

The International Institute provided its students with a one-year language course to prepare them to go on to Hungarian Universities. Up to the beginning of December we all followed the same curriculum, an introduction to the basics, after which we were redistributed into groups which were largely of a vocational nature - medicine and engineering for example, in which language continued to be taught through the medium of the specialised subject, along with a fair amount of the subject itself. By these means, the Soviet Colonial Empire, which spent its days accusing the West of Imperialism, intended to colonise the world through the dissemination of ideology and the provision of services.

The students were largely there for overtly political reasons (or not, as in the case of the Czechs). Patrice Lumumba, the eponymous son of the Congolese leader assassinated in 1961, told me that he had several brothers and sisters distributed around different Eastern European countries for educational purposes.

The trivial round, the common task, was pretty bad. Lessons began at eight and continued all morning, with a short break, and another later for lunch. The food was beastly and tasteless, but it was better than the toilets, which were unspeakable and you had to bring your own paper. There was a notice in English requesting "PLEASE DO NOT URINE ON THE FLOOR." By early afternoon, lessons were over.

The curriculum was at this early stage nothing more than a military style drilling in Hungarian, enlivened only rarely by moments of farce. Someone wanted to know the meaning of the Hungarian expression, "mit jelent?" [what does it mean?]

S: [In Russian] What does it mean - 'mit jelent?'

T: It means: 'what does it mean?

S: I don't know: what does it mean?

T: 'What does it mean?'

S: Well I don't know - that's why I'm asking you. [Back to line 2]

And so on. Although Hungarian is notoriously difficult, I found learning it comparatively easy, perhaps because a whole language, long dormant in my unconscious, was being awakened. Ere long Mrs Maroti would be parading me publicly as evidence of the success of her teaching methods, and doubtless the over-fulfilment of the five-year plan for the dissemination of the Hungarian language throughout the universe.

As for politics, I tried to keep my nose as clean as possible, but it wasn't altogether easy. Attendance at political events was compulsory and distasteful; for example, there were celebrations to mark the twentieth anniversary of the DDR - the so-called German Democratic Republic - which was neither democratic nor a republic, although it did contain Germans: East Germany, in other words.

We had to watch some pretty grim films. No matter how hard the cameraman tried, no photographic skills could mask the unrelieved grimness of the serried ranks of Stalinist tower blocks.

There was also a whole evening to which the various national groupings each contributed poems and songs to mark the anniversary. The Nigerian piece was in one of their languages with a chorus in Hungarian at the end of each verse. The chorus was very straightforward:

Szervusz, szervusz!;

Szervusz, szervusz!;

Viszontlatasra! [Hello x 4 and Goodbye]

I wanted to know what the rest meant. My friend Tundi translated. It was just as well that the authorities, who had been sold some bullshit about the courage of the glorious East German workers, could not understand. To quote just one line, representative of all the rest; "I'd like to screw all the girls in Buda."

However, lip service had its limits. I soon got into trouble for not attending two compulsory events; the first involved filing past the coffin of a writer who, although a fine classical scholar, had become too much of a lackey of the regime for my taste.

The second occasion was, however, much more serious; I missed the trip to Dunaujvaros (Danube New Town, formerly Stalin new Town), a model of communist industrial development and boredom. I stayed in bed revising irregular verbs whilst the others had the pleasure of an insight into the wonders of socialist planning.

I was duly summoned to the office of the Principal, where I anticipated terrible reprisals. Instead, I found a kindly gentleman who courteously invited me to sit down.

"Is your father in good health?" was the first question.

There followed a classic request. Did I, by any chance, have a copy of the Villon Ballads? Truthfully, I answered that I did not. The conversation went on for quite some time. I was convinced then, as I am now, that this was not some kind of a trap. He was just a genuinely good chap. When it was time to go I felt a twinge of regret for having inconvenienced him.

Then, as I opened the door, he called me back.

"Oh, by the way, my dear András. About yesterday. In future, don't be so bloody stupid!"