Hungary’s New Opposition is Not Only New but Also Politically Astute

Members of Hungary’s new opposition rightly recognised the Hungarian public’s frustrations with established parties. They were also proven to be shrewd political actors.

This year’s European Parliamentary and local elections in Hungary will go down in History as one that radically restructured the country’s political landscape and introduced us to skilled new politicians.

Underperforming Fidesz

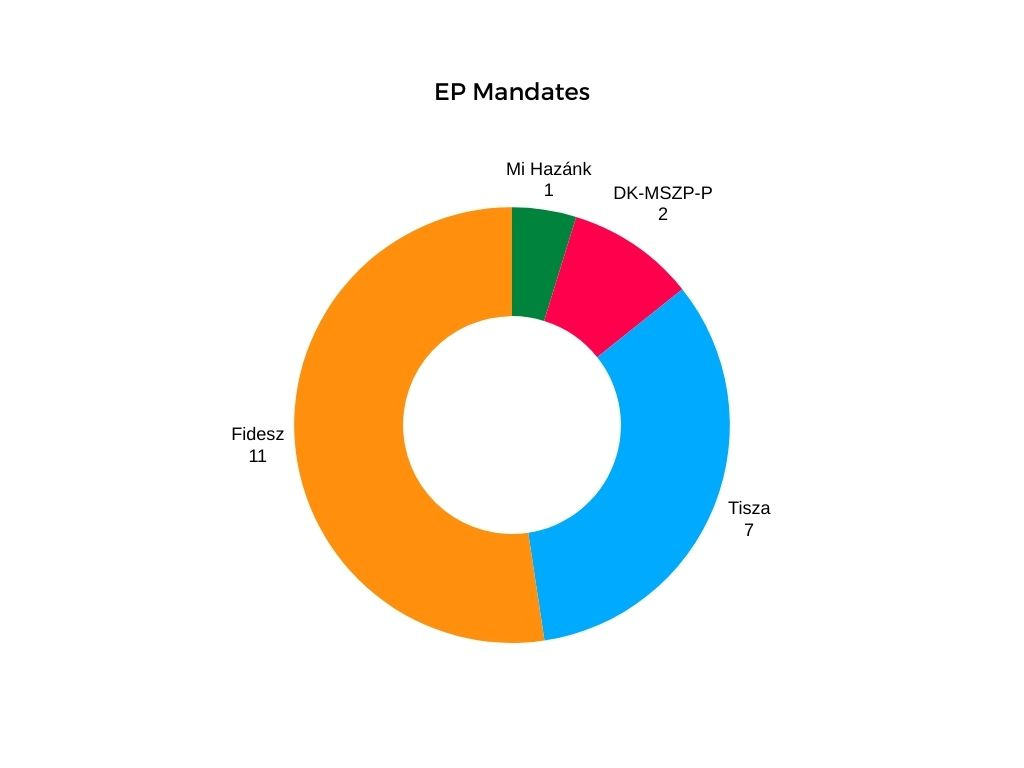

Fidesz produced its worst result since 2006 and its worst-ever result at European elections. This still means that they gained 11 seats in the European parliament but Viktor Orbán’s goal of the “greatest-ever” mobilisation campaign failed to meet his expectations.

They ended below the 45%, an arbitrary but symbolic threshold. In the local elections, they gained 575 fewer councillors than in 2019 (though some of these are simply due to Fidesz affiliates who ran in independent colours). Crucially, their vote share also decreased in all counties in the County Council elections, a key indicator of a loss of support for them in smaller settlements, their no1 stronghold.

Despite all these statistics, it is worth bearing in mind that Fidesz is, by a healthy margin, still the largest party in the country and managed to gain more than half of the country’s EP seats. Additionally, this was at an election that directly followed their greatest-ever crisis in the form of the clemency scandal that cost them two of their most prominent figures and dealt a major blow to the authenticity of their own messaging about family protection.

Despite all this, it is apparent that Fidesz view the results as a failure. This was clear from the faces of their politicians on election night. Another key indication of this is that a few days after the election, there was a marked change in Fidesz’s attitude to the part of the Hungarian public that is otherwise critical of them. On Wednesday, Viktor Orbán gave an interview to Index which, though influenced by the government since 2020, is read by plenty of opposition voters too. The same day, government minister Gergely Gulyás gave a visit to the Fidesz-critical euthanasia campaigner Dániel Karsai who is suffering from ALS. Another government minister, Antal Rogán, gave an interview to the liberal news outlet 444 on Thursday.

Flooding Tisza

The reason for their worries is the performance of Péter Magyar’s new political party, Tisza. Tisza managed to gain almost 30% of the votes and are about to send 7 MEPs to the European Parliament and join the EPP. Magyar’s party decimated the existing opposition as the DK-MSZP-P left-wing alliance will only send 2 MEPs instead of the 5 they had in 2019, and liberal Momentum, who had 2 MEPs since 2019, is now out of the European Parliament.

However, Fidesz are not worried about Tisza because Péter Magyar is shoring up existing opposition votes. It is their results in major cities outside Budapest that can potentially give Viktor Orbán some anxiety.

According to Választási Földrajz, Fidesz produced the greatest degree of loss in vote share in cities with County Rights (where Fidesz’s vote share declined by 9.3%) and in cities with a population of 20.000 or more (also -9.3%). Crucially, Tisza produced their best results not in Budapest (where they gained 32.8% of the votes) but in cities with county rights (35.1%) and cities with a population of 20.000 or more (34%). This is an indication that Tisza can snatch at least some voters from Fidesz, a feat many of Péter Magyar’s sceptics, including many of us at this outlet, did not think he’d be able to pull off.

Tisza actually managed to outright beat Fidesz in Nyíregyháza, Szeged, Szolnok, and Dunakeszi. Or look at the results in Debrecen, Fidesz’s most iconic stronghold. Fidesz gained 40.69% of the votes while Tisza came close second with 37.49%. Here, in the 2022 general election, Fidesz’s candidate, Lajos Kósa, won 48.95% of the votes and the United Opposition’s Zoltán Varga gained 39.75%.

Magyar still has a long way to go until 2026 when he will need to convince even more Fidesz supporters to vote for his party while keeping his current opposition-heavy base. This won’t be an easy task and it is far from clear that he will be able to do this. The hype that surrounded him in the past four months is very unlikely to last until then and we still don’t know virtually anything about his candidates who were elected.

But four months ago no one knew who Péter Magyar was and Tisza, at present, has no organised party structure. And yet, they managed to produce an outstanding result. Magyar’s political judgment about being wishy-washy about the Ukraine war, ignoring criticism from mainstream liberal media, and carefully mixing cultural reference points from both the right- and left-wing canons is working so far. Touring smaller towns and Fidesz strongholds also seems to have paid off. Magyar’s further success is not guaranteed but this election showed signs that his plan could potentially work.

Karácsony’s miscalculation and Vitézy’s shrewd tactical change in Budapest

The most exciting race on Sunday unfolded for the mayoralty of Budapest. Dávid Vitézy, a former secretary of state under the Fidesz government but this time running in LMP colours, was leading throughout the night. But in the very end, Gergely Karácsony won the race by only 324 votes. The result is still not 100% sure because Vitézy has requested a partial recount which is taking place today. He claims that a number of his votes were incorrectly marked as invalid.

It is a rather complicated matter but the situation is essentially as follows: Fidesz’s candidate Alexandra Szentkirályi withdrew from the race at the last minute so her name was crossed out on the ballot papers. Some Fidesz sympathisers put an X in the circles by both Szentkirályi’s and Vitézy’s names. Had Szentkirályi still been a candidate, this would have indeed been an invalid vote. However, as she withdrew, her name on the ballot box was supposed to be considered non-existent, meaning that a vote like this for Vitézy still stands. The X by Szentkirályi’s name is no different than a doodle on the ballot paper. As the Hungarian Observer and other Hungarian media outlets understand, this has happened frequently and at some polling stations, counters did mistakenly consider these invalid. The only question is if it happened in more than 323 instances or not.

First thing’s first, the only reason such a tight result was possible is because Fidesz withdrew their candidate at the last possible minute. This was relatively unsurprising as it had been rumoured for a while and Gergely Karácsony built his entire campaign on loudly repeating this possibility.

But even in this scenario, Karácsony was expected to win much more comfortably. The fact that he did not can be attributed to two factors: the usually politically astute Karácsony’s miscalculation and Vitézy’s clever change of tactics towards the end of the campaign.

Karácsony’s miscalculation was that he failed to realise just how much the Hungarian opposition-leaning public is fed up with the old opposition parties, especially former Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány’s DK. Karácsony’s schtick has always been that he was able to be the bridge between the old opposition parties MSZP and DK and the new ones, be they LMP, Párbeszéd, Momentum, or Péter Márki-Zay. This is how he became the mayor of Zugló in 2014, a prime ministerial candidate in 2018 and 2021, and crucially the mayor of Budapest in 2019.

However, anti-Orbán Hungarians no longer want to cross this bridge. They want to burn it. Karácsony should have known this, especially since an early manifestation of this sentiment was exactly why he was beaten by Péter Márki-Zay in the United Opposition’s 2021 primary.

There were several opportunities for Kárácsony to reposition himself for this election but he failed to do so. Momentum announced at the beginning of the year that they would contest the Budapest Assembly elections separately without DK. A lifeboat for Karácsony was presenting itself. Terézváros’s Momentum mayor Tamás Soproni, Józsefváros’ Momentum-affiliated mayor András Pikó, and Ferencváros’ MKKP-affiliated mayor Krisztina Baranyi all told the YouTube channel Partizán that they were in favour of contesting the Budapest Assembly elections together in the form of an independent list of mayors without party logos led by Karácsony.

He rejected the offer and opted to run on a DK-MSZP-P list, an alliance that also contested the European Parliamentary elections which resulted in Karácsony appearing in several posters all over Budapest side-by-side with Klára Dobrev, one of the most controversial politicians among opposition voters.

Alongside constantly highlighting how he thinks Szentkirályi would withdraw from the contest, Karácsony also ran an identity politics-focused campaign in which he claimed to protect the liberal island of Budapest from the oppressive illiberal Fidesz government. However, he did this exclusively in DK-MSZP-P's old opposition colours.

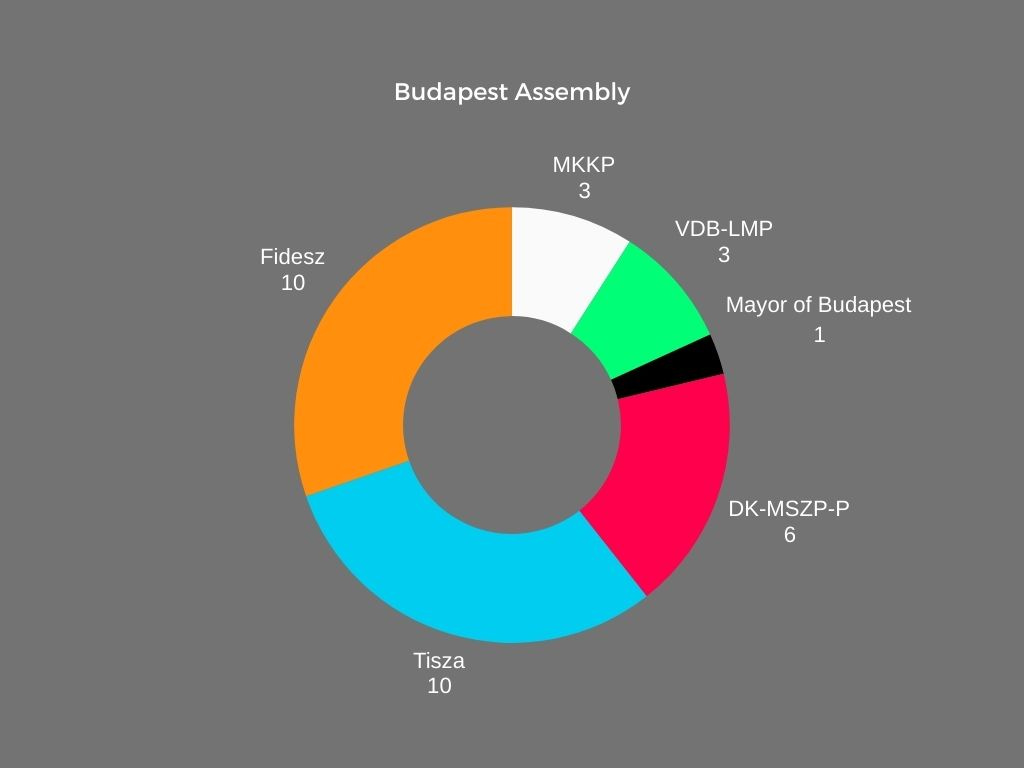

This opened up a huge opportunity for Dávid Vitézy. He started his campaign as the “technocratic expert” candidate. After Péter Magyar’s emergence, however, Vitézy rebranded himself as Budapest’s version of what Tisza is doing nationally. He said that he wanted to build a majority in the assembly without Fidesz and DK with the help of Tisza, LMP, and MKKP (which, by the way, is perfectly possible based on the final results), thus managing to utilise both Budapest’s anti-Fidesz vote as well as the country’s anti-established-opposition sentiment. That the latter was possible was an entirely self-inflicted weak point of the Karácsony campaign.

Utilising these circumstances was a rather shrewd move by Vitézy, a man who is completely new to party politics. It would be interesting to know if it was his idea or the idea of LMP’s leader and Vitézy’s number one campaign donor, billionaire Péter Ungár, a rather experienced and skilful political operator. Whatever the case, Vitézy executed the plan perfectly, and even if the current results remain, he exceeded expectations massively. He won the vote in 13 districts out of the 23 and is not in a bad position for the 2029 mayoral elections.

During his career, Karácsony has made mistakes and suffered defeats before due to losing his nerve, not being decisive, or simply not being popular enough. But in this campaign, for the first time in a while, he was simply outmanoeuvred politically.

That being said, if the result does indeed hold, we should not underestimate Karácsony either. After all, he was vindicated in his prediction about Szentkirályi withdrawing in favour of Vitézy, an often repeated mantra whose mobilising power likely won him the mayoralty in the end. The complicated composition of the new Budapest Assembly (where no party has a majority) suits his skills as an experienced deal breaker and a man of compromise. His campaign starting yesterday in which he claims that he wants to redo the mayoral elections even in case he wins is a sign that he still has a few political tricks up his sleeve.

MKKP’s mixed but overall positive night

They held two elections at the same time in Hungary last Sunday. European Parliamentary Elections and local elections. MKKP’s performance on the former was a clear disappointment. With 3.57% of the votes, they failed to reach the crucial 5% threshold to be able to delegate one MEP to the European Parliament. For a party that was polling as high as 11% in March, this is a clear disappointment. They were even overtaken by Momentum, a party in the middle of a collapse, in the race for the urban progressive vote. This was the election where MKKP was set to establish itself nationally but they failed to do this.

Part of this was the result of the Magyar-Tisza phenomenon. Research by 21 Kutatóközpont suggests that MKKP was the party whose largest share of intended voters defected to Tisza. According to the pollster, 57% of those who formerly intended to vote for MKKP ended up voting for Tisza. Party leader Gergely Kovács also admitted that they failed to find a theme for the campaign as the European Parliament is perhaps the most alien institution among the three different types of elected office in Hungary for the grassroots campaign and localism-oriented Two-Tailed-Dog Party.

Worringly for them, if Tisza’s popularity remains, the draw of the party might prevent them from exceeding the 5% once again at the national elections in 2026, where voters are even more likely to vote tactically, especially if a change of government seems possible. A tiny silver lining for MKKP at the European election is that it is still true that the party has managed to increase its vote share in every single election it contested. This time from 3.27% in 2022 to 3.59% in 2024.

However, despite their disappointment at the European elections, the Dog Party were arguably the biggest winners of the local elections. They won all their target seats and exceeded expectations by gaining 51 council seats, 3.4 times more than the 15 they had in 2019. Only Mi Hazánk (who came second in all but two county council elections) managed to produce a larger increase. They gained 158 seats, compared to 34 last time, however they failed to produce any mayors, which is a setback compared to the two they had in 2019.

The Dogs, on the other hand, won their long-desired prize: their leader, Gergely Kovács, will be the mayor of Budapest’s District XII. They and their local allies (2 Momentum councillors and a local independent) won in every single ward in the district and the Dogs even have a majority in the council without their allies; they can do whatever they want in the wealthiest district of Budapest.

Krisztina Baranyi, a leader of their Budapest list, also won in Ferencváros district and all of her councillor candidates (a large portion of whom were MKKP candidates) won their races in their respective wards as well.

The victories of Baranyi and Kovács are not only a result of hard grassroots work, but also of calm and skilful political manoeuvres. Both MKKP mayors fought off not only Fidesz candidates but members of the old opposition as well. They chose different strategies for this; Kovács agreed to participate in an opposition primary but only if his conditions were met and the winners would not have to use the losers’ logo and, crucially, if the winner would also be able to nominate councillors from their party in individual wards. This was a good enough deal so that MKKP could not be accused of uniting with other opposition parties while avoiding the split of the anti-Fidesz vote at the same time. In the end, the fact that DK did not adhere to the agreement and had candidates in wards only benefitted Kovács in distancing itself from the old opposition.

Baranyi faced a larger and slightly different threat. In her previous five years as mayor, she fell out with several councillors in her former team. These councillors contested seats against her semi-new team of loyal councillor candidates. Additionally, apart from Fidesz’s mayoral candidate, she also simultaneously had to face Ferenc Gegesy, her former advisor and former mayor of Ferencváros for the mayoralty. Baranyi could have easily folded and agreed to negotiate to have councillors from the older opposition parties (MSZP and DK) as part of her new team in exchange for Gegesy’s withdrawal. But she called the old guard’s bluff and ran anyway and won comfortably with a team composed of loyal councillors.

Other than the mayors, MKKP will also have 2 councillors in several Buda districts and in Újpest, as well as a councillor in many other Budapest districts. They are delegating three councillors to the Budapest Assembly, where due to its composition, they are guaranteed to be kingmakers. But even better news for them is that they will also have several councillors outside Budapest, including 2 each in Szeged and Székesfehérvár, one in cities such as Eger, Pécs, and Veszprém, and, crucially, a number of councillors in tiny villages as well, such as Vöröstó, a village with a population of 104. Another good result for them in the country is that they came third in County Fejér (the only county where they contested the County Council elections). With 2 councillors, they are the largest non-right-wing party (beating Momentum and DK) there.

MKKP, Dávid Vitézy, and Péter Magyar were all proven to have fine political judgement during the course of this campaign. Hungary’s New Opposition did not only succeed at this election but, as their different stories show, did so by proving themselves to be skilled political operators in the process.

Ábel Bede